Published June 13, 2022

Beauty in the Bones

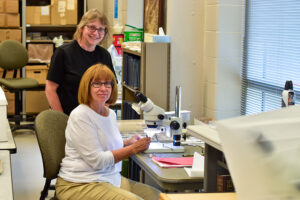

Eight to 10 hours a week, when they could be doing anything they want to, Deborah Patrick and Susan Brutkiewicz can be found in the Indiana State Museum’s Ronald L. Richards Natural Sciences Lab identifying microscopic bones excavated from Megenity Cave in southern Indiana.

Eight to 10 hours a week, when they could be doing anything they want to, Deborah Patrick and Susan Brutkiewicz can be found in the Indiana State Museum’s Ronald L. Richards Natural Sciences Lab identifying microscopic bones excavated from Megenity Cave in southern Indiana.

Both retirees – Patrick was a family doctor; Brutkiewicz a research scientist with a doctorate in molecular and cell biology – are volunteers at the museum. For them, that means taking small, clear plastic boxes containing microfauna, putting the contents under a stereo microscope, determining what they’re looking at and then sorting the contents into one of 26 designations.

They’re looking at the skeletal remains of snakes and lizards, birds, mice and voles, fish, woodrats and other creatures that ended up in the cave southwest of Corydon for one reason or another 11,000 or more years ago during the Ice Age.

“It’s fun,” Brutkiewicz says. “At first, I found it almost intimidating – there was so much more to it than I thought. When I came here, I thought I was going to be cleaning mastodon bones or something. I had no idea what was going on on this end.”

For 30 years, Senior Research Curator of Paleobiology Ron Richards led archaeologists, paleontologists and others on digs at Megenity Cave. (Richards died in March 2021.) They dug up hundreds of thousands of fossils and animal bones – some large, some medium and many, many tiny ones. All need to be cataloged to help scientists determine how Indiana’s climate and habitat has changed.

For 30 years, Senior Research Curator of Paleobiology Ron Richards led archaeologists, paleontologists and others on digs at Megenity Cave. (Richards died in March 2021.) They dug up hundreds of thousands of fossils and animal bones – some large, some medium and many, many tiny ones. All need to be cataloged to help scientists determine how Indiana’s climate and habitat has changed.

Brutkiewicz got involved in the cataloging process four years ago when someone in a rock club that she belonged to suggested she talk to Richards.

Patrick was a structural biology teaching assistant as an undergraduate and always enjoyed working with the microscope and making discoveries in the lab. Her husband, Randy, another of the 10 volunteers who work in the lab regularly, had worked with Richards for years. After Patrick retired in early 2020, she joined him as a volunteer.

“There’s no sick people here,” she said. “I’m not going to make anybody cry today” with bad news. “In medicine, there’s always a degree of uncertainty. What I liked about coming here when Ron was alive was that he would sit down with us at the end of the day for an hour or hour and a half and go over every bone. I felt I knew what it was. And if Ron didn’t know what it was, there wasn’t anybody in the Midwest who knew what it was. I like that level of knowledge, that assurance.”

Both Patrick and Brutkiewicz say it took about a year to be able to tell the bones apart. “The more you learn, the more fun it becomes because you’re not overwhelmed when you look in the box,” Brutkiewicz says. “You know what 90 percent of the things are.”

Both Patrick and Brutkiewicz say it took about a year to be able to tell the bones apart. “The more you learn, the more fun it becomes because you’re not overwhelmed when you look in the box,” Brutkiewicz says. “You know what 90 percent of the things are.”

“A lot of it is pattern recognition,” Patrick says.

That said, there are always mysteries. Always new finds too. One day in May, Brutkiewicz found a molar from a marten, a weasel-like mammal that now are found in the far-northern United States, Canada and Alaska.

“I knew it was a carnivore of some kind and I knew roughly the size of the animal,” she said. “We have a huge reference collection of every Indiana animal that there is, so I compared it and matched it up.”

“I look at it like every box is a puzzle,” Brutkiewicz says. “There are going to be some obvious ones and then there are going to be some tough ones.”

Whatever the situation, both say they enjoy working in the lab and learning more about how Indiana has evolved over the ages.

“I think this is a beautiful lab,” Patrick says. “I love this room and being able to sit and look out over the canal.”

“And look at our surroundings,” Brutkiewicz says. “We have this petrified chunk of wood here with a geode inclusion. We have this Bryozoa fossil. There’s always this neat stuff that’s interesting to learn about that we never would have seen or known about otherwise. It’s always fun.”