Published October 29, 2021

Spookiest items from the museum’s collection

The permanent collection of the Indiana State Museum and Historic Sites contains more than 500,000 objects, from tiny archaeological finds to massive mastodon skeletons. The collection spans across topics, including paper artifacts, pop culture, furniture, clothing and just about whatever else you can imagine.

Together, these objects tell the story of Indiana and the Hoosiers who have shaped the state.

But, the history of Indiana isn’t always cheerful. Sometimes, it’s downright spooky.

Ahead of Halloween, the museum’s curators dug through the collection to find some of the creepiest things we have – and to share those items from behind-the-scenes with you, as many aren’t on display.

From caskets to embalming tools, here’s some of the eeriest items we have.

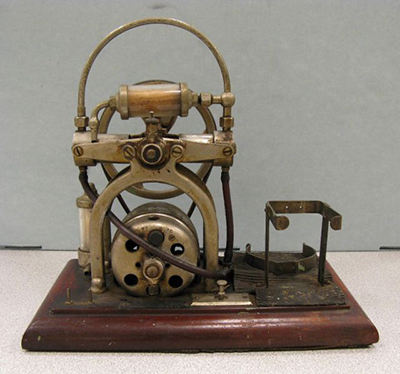

ELECTROTHERAPY MACHINE

From the 1700s through today, electrotherapy has been used on people suffering a variety of ailments, including tuberculosis, epilepsy, seizures and more. This electrotherapy machine from 1850 was used to deliver electric shocks to people who either held the electrodes or had them placed on their bodies. The machines were often purchased for personal use. A voltage of 1.5 volts could be produced by the machine’s battery – enough volts to power a flashlight or remote control today. In current times, electrotherapy is used by some for pain management.

HAIR ARTIFACTS

During the 1800s, it was common for people to create jewelry or wreaths from the actual human hair of their loved ones. Sometimes this was done upon a loved one’s death in order to commemorate them, and sometimes it involved living relatives. The hair wreath above, for example, was made by Esther Hall Hyde with hair from each of her 12 children woven together. We have 12 hair wreaths in our collection – but you can see a real hair wreath for yourself in our Level 2 galleries.

INDIANA FUNERAL DIRECTORS ASSOCIATION COLLECTION

We have an entire collection from the Indiana Funeral Directors Association – including the cooling board. Undertakers used these cooling boards from the 1880s to 1940s, when funerals took place in homes. A block of ice was placed under the board to cool the body, and the holes drilled in the table enabled better air circulation to prevent unfortunate smells.

The electric embalming pump (above) is from 1920-30 and is also a part of The Indiana Funeral Directors Association Collection. The way it works is that the motor turns the metal wheel, and rubber connecting tubes feed the embalming fluid into and out of the body. Embalming fluid preserves a body for many years, even after burial. In our collection, we also have embalming fluid, tools and other artifacts commonly used for funeral services dating back to the mid-1800s.

DEATH MASK

That’s right – this is a painted plaster “death mask,” depicting an unknown older woman. Death masks were plaster casts taken of a dead person’s face, then painted to look like them and hung on a wall or otherwise displayed. If you look closely, you can see the rope loop strung through the back of the mask in order to hang it. Masks were used as memorials of the dead from the Middle Ages through the 19th century. Along with memorials, they’ve also been used as models for painters and sculptors to use after someone’s death and, prior to photography, they were used by police to help identify victims.

Casket

Indiana is the leader in casket-making, thanks to Batesville Casket Company. The company began in 1884 as the Batesville Coffin Company and is still in operation today. The casket shown is a child’s coffin made by undertaker and cabinetmaker Henry Rupp of Harrison County between 1875 and 1900. A removable oval plate on the front allowed the family to view their loved one’s face one last time before burial. You can see this coffin for yourself in our Level 2 galleries.

GRAVESTONE AND TABLE

The table shown originally served as a real tombstone in the 1830s or 40s for Margaret and William Maclure, two siblings who lived in New Harmony, Indiana. William Maclure was a well-respected geologist in his day, and he was also a business partner with Robert Owen – a man who attempted to create a utopian community in New Harmony in the 1820s. Sometime between 1879 and 1890, the gravestone was removed and sold to a print shop to be used as an imposing slab. The table was used in the print shop in Community House 2, and today, visitors will find another person’s tombstone there: Thomas Say, the father of North American entomology and discoverer of Say’s Firefly, which became Indiana’s state insect in March 2018.

We aren’t sure why the tombstones were converted – most likely, it was simply an economical reuse of good materials, since the stones provided a nice flat surface for printing. The Maclures and Say are still buried in New Harmony, with new tombstones.